Someone with fiduciary responsibility is meant to act in your best interest — a promise of loyalty, prudence, and care.

In principle, your advisor’s first obligation should be your financial well-being.

In practice, the incentives often point elsewhere.

Larry Kotlikoff, a professor of economics at Boston University, puts it bluntly: “The industry’s practices violate any reasonable economics-based fiduciary standard.”

He argues that much of modern financial planning ignores economic reality, leading to poor advice about saving, insurance, and portfolios.

That failure isn’t abstract — it shows up in real people’s lives.

Pension Plan Nightmare

As soon as I left Oxford University with an MA in Math, I was confronted by the absurd math of conventional financial planning.

One of my first assignments in the early 1980s was to prepare “audits” of Defined Benefit Pension Plans. These audits were a government requirement, intended to verify that corporate pension promises were properly funded.

It didn’t take long to see the problem. The assessments were arbitrarily constructed.

“Plausible” assumptions (about salary growth, investment returns, and life expectancy) could produce almost any result the preparer wanted.

The incentives made it worse. The Actuary wanted to keep the client happy and win repeat business. The CEO wanted to show lower pension costs on the company’s balance sheet.

Together, that meant the “good” result, based on the best-case plausible assumptions, usually won.

It was therefore inevitable that pension funds would be systematically underfunded.

A decade later, when it was “discovered” that most defined benefit plans couldn’t meet their obligations, they were shut down and replaced with Defined Contribution Plans.

Who could have guessed?

The Lesson is Never Learned

The tragedy of that pension debacle is that the lesson was never learned, and so the same mistakes continue today.

Now it’s not corporations that are underfunded; it’s individuals, left with fewer savings, fewer protections, and financial plans that still escape the scrutiny they desperately need.

The conventional financial plan has simply moved from the actuarial office to the advisor’s desk. The process looks remarkably similar, only now it’s run by professionals who are often less qualified than the actuaries to run the same process.

What passes for a “fiduciary plan” today can even allow a 20% chance of bankruptcy in a retiree’s lifetime. That would never have been acceptable in a corporate pension. And it shouldn’t be acceptable for an individual’s future either.

Too often, the plan becomes a gamble based on bad math: complex models producing confident-looking numbers that neither the advisor nor the client fully understands. Just because software prints a figure doesn’t mean it’s useful, no matter how many pages of charts accompany it.

The result is a system that gives the illusion of precision while offering unreliable accuracy and almost no ability to truly optimize the difficult trade-offs retirees face at the most crucial financial stage of their lives.

Discovering the Real Problem

I left the pensions consultancy as soon as I could and spent the next few decades as an investment professional. During that time, I stayed far away from conventional financial planning.

Then I discovered the work of Larry Kotlikoff, a professor of economics at Boston University, and his financial planning software, MaxiFi. It was a game changer. For the first time, it was possible to see what best practice could look like — a plan that begins with accurate data, informed consent, and virtually no arbitrary assumptions. It became the foundation for what I now call Comprehensive Wealth Management.

Kotlikoff’s research names the problem directly: most financial planning advice violates the basic principles of economics.

Traditional planning tries to answer isolated questions — How much should I save? When can I retire? How much can I spend? — using projections that have little connection to how households actually live or make decisions. The result is advice that looks quantitative but ignores the full economic picture.

According to Kotlikoff, the industry’s methods fail a true fiduciary test for three reasons:

- They optimize the wrong goal. They focus on portfolio performance or “probability of success” instead of lifetime living standard.

- They rely on guesswork disguised as precision. Small changes in return or inflation assumptions can flip the outcome from safe to ruinous.

- They ignore the household as an economic unit. Taxes, benefits, and spending patterns aren’t coordinated, even though they determine real-life outcomes.

In Kotlikoff’s view, a plan that neglects these realities isn’t just inefficient.

It’s a breach of fiduciary responsibility.

That diagnosis reframed everything for me. It clarified what was wrong with traditional planning and pointed toward the only credible solution: an economics-based approach that measures and optimizes what actually matters in people’s lives.

MaxiFi Financial Plans

Without a credible financial planning tool, Comprehensive Wealth Management isn’t credible either. Once I discovered MaxiFi, I could finally see a clear path to best practice — one grounded in real economics, informed consent, and measurable results.

What makes MaxiFi different is its foundation in lifecycle economics, a body of research developed by some of the most respected economists in the world. In their landmark book Lifetime Financial Advice, researchers Paul D. Kaplan and Thomas Idzorek describe exactly how conventional financial planning and investment advice must change to align with that science. Their work draws on the theories of eleven Nobel laureates in economics, along with pioneers such as Irving Fisher, John von Neumann, Oscar Morgenstern, and Menachem Yaari — all of whom contributed to the equations that define economics-based financial planning.

MaxiFi’s software jointly solves those equations. It doesn’t rely on arbitrary assumptions or one-size-fits-all rules of thumb. Instead, it models the household as an integrated system — income, spending, taxes, benefits, and risk — to determine how families can maintain the highest possible lifetime living standard given their real-world constraints.

The platform has even earned recognition in academia. Robert Merton, a Nobel laureate and professor at MIT, teaches MaxiFi in his graduate Asset Management course. As Merton puts it:

“I assign MaxiFi Planner in my Asset Management Course at MIT’s Sloan School of Management as an outstanding science-based lifecycle and retirement management platform.”

When I saw that level of intellectual and scientific support behind a planning tool, it confirmed what I had long suspected: the future of fiduciary financial advice will be based on sound economic principles, not convenient assumptions.

MaxiFi made it possible to bring that future into practice. And it allows us to build real, comprehensive wealth management around facts.

Putting It All Together

If a fiduciary is meant to act in your best interest, then a financial plan that ignores economic reality cannot meet that standard.

For decades, the industry has replaced rigorous, economics-based planning with assumption-driven projections — plans that look scientific but fail to measure what truly matters: your sustainable lifetime living standard. The consequences have been profound, from underfunded pensions to individuals forced to gamble their futures on bad math.

There is a better way.

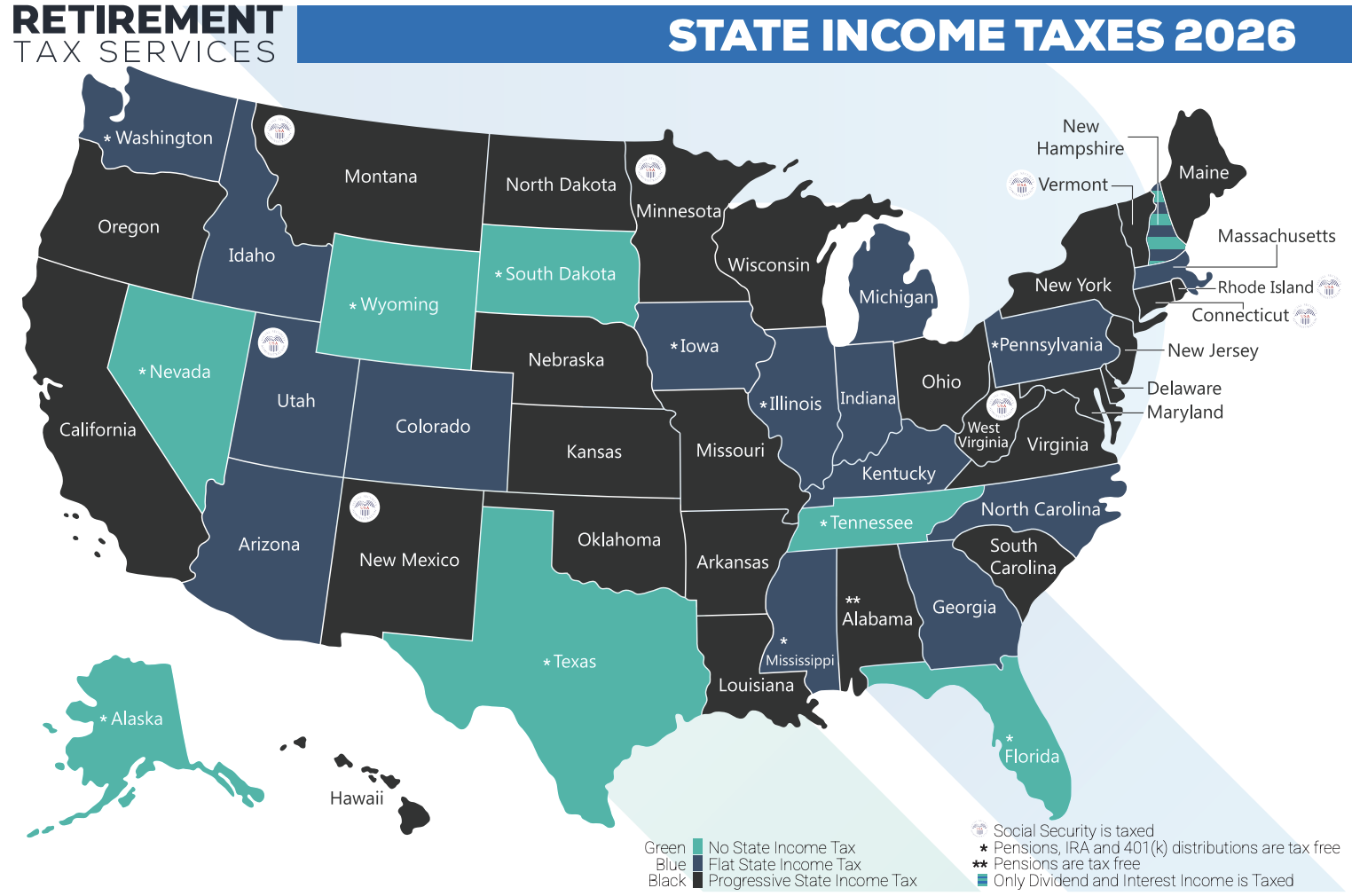

Economics gives us the framework. MaxiFi provides the tool. Comprehensive Wealth Management delivers the process. Together we can align taxes, benefits, spending, and investments under one unified plan.

This is what being a fiduciary should mean in practice: advice grounded in real data, optimized for lifetime outcomes, and transparent enough for every client to understand.

So ask yourself: Is your financial plan really in your best interest — or just presented as if it were?

Because the answer to that question determines far more than your portfolio. It determines your freedom, your security, and your confidence in the years ahead.

The good news is that you can rebuild on a stronger foundation.

That’s what best practice financial planning is all about.