The story of infinite progress is a powerful one.

We want to believe that markets evolve, technology advances, and human ingenuity outsmarts every limitation. It’s comforting, this idea that things always move up and to the right.

But belief can be blinding. The more we emotionally invest in the story of endless growth, the harder it becomes to see its flaws. And the more complicated our systems become, the easier it is to hide simple truths.

Nowhere is this truer than in modern finance. Layered with mathematical abstractions, acronyms, and legalese, the system feels too complicated to understand.

Yet the man perhaps most responsible for shaping our current system understood finance with one simple truth:

“Gold is money. Everything else is credit.”

— J.P. Morgan

The Founding Irony — J. P. Morgan and the Birth of the Fed

In 1907, when the Knickerbocker Trust collapsed, confidence vanished overnight. Depositors lined the streets, stock prices plunged, and credit froze. With no central bank, no emergency playbook, and no government backstop, the country turned to one man with the capital and the resolve to decide who would survive.

From his library on Madison Avenue, J. P. Morgan summoned the heads of New York’s largest banks and trust companies. He studied their books, weighed their collateral, and according to legend, locked the doors until they pledged enough money to stem the panic. By dawn, the market had a lifeline.

Morgan stabilized the system, but he also revealed its flaw. A financial order that could only be saved by the will of one private citizen was not a stable order at all.

He understood the danger of unchecked credit. However, his goal was to create a mechanism that would share the burden of responsibility.

Six years later, Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act of 1913, creating a central bank designed to prevent the next panic. The Reserve Banks would be regionally governed by commercial bankers, not by elected officials. What began as a safeguard became an engine for managed credit, an institution able to expand money and debt at will.

The intent was stability, but the new tools of credit dulled discipline. Risk no longer ended in ruin; it ended in intervention.

The system built to prevent market crashes only served to kick the can down the road, making the credit cycle even bigger. It replaced the restraint of gold with the elasticity of credit, ensuring that each generation would push the limits further until the same cycle returned: expansion, excess, and a larger crash.

And that is the founding irony.

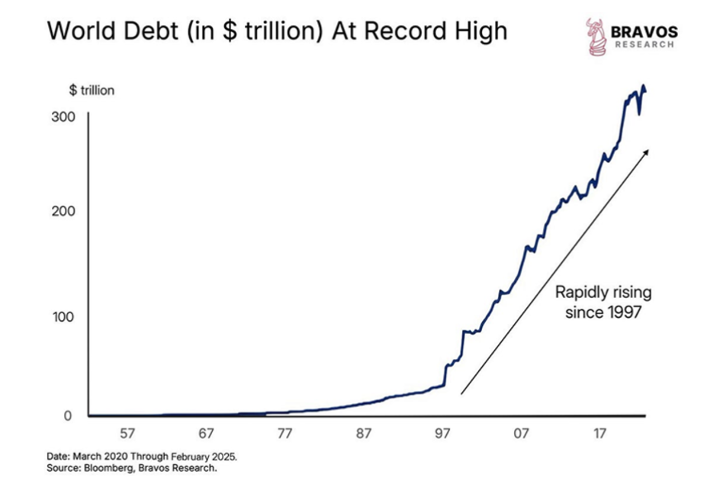

With credit now globalized, it’s no surprise that debt has grown without limit.

The Incentive Engine — How the System Manufactures Instability

“Show me the incentive, and I’ll show you the outcome.”

— Charlie Munger

If the Federal Reserve institutionalized credit, the banks weaponized it. Once money could be created with the stroke of a pen, profit became a question of how much leverage the system could bear. Every new type of trade (derivatives, mortgage-backed securities, credit default swaps) was another layer built on promises stacked atop other promises.

The results were predictable. In an incentive structure where gain is private but loss is socialized, restraint becomes irrational.

Heads they win; tails you lose. It’s the same game of Monopoly everyone knows, except the banker is both player and rule-maker.

Banks discovered that risk wasn’t something to avoid; it was something to price. And once risk could be sold, it could be multiplied. The modern financial system became a machine for manufacturing returns out of borrowed confidence, its complexity serving as camouflage for its fragility.

Meanwhile, policymakers learned a parallel lesson. Every time intervention prevented collapse, it also validated excess. Lower interest rates encouraged more borrowing; higher asset prices justified more speculation. Each bailout, from Long-Term Capital Management to 2008, taught markets that getting rescued was part of the playbook.

The deeper the safety net, the greater the fall it invites. What began as a tool to stabilize commerce evolved into an engine of instability, driven by perfectly rational behavior inside a perfectly misaligned system.

When people are paid to extend risk, they will extend it. When institutions are bailed out after failure, they will fail bigger.

We’ve Seen this Movie Before — Literally

Every generation convinces itself that “this time is different.”

The technologies change, the assets change, the language of excess evolves, but the pattern never does.

The setup is always the same: easy money, expanding credit, and the belief that this can go on forever. For a while, it works. Debt feels like prosperity, speculation looks like innovation, and the rising line on every chart seems to prove that the system always recovers.

But there’s a catch.

It’s easy to show the market moving up and to the right when value is measured in dollars, because the institutions controlling the dollar supply can print more. When more dollars chase the same assets, prices rise even if real value doesn’t. It’s not genuine growth; it’s monetary inflation masquerading as progress.

That’s why each cycle ends the same way. Eventually, the illusion breaks. The money supply can grow faster than productivity, but eventually there’s a reality check and the market correction begins.

We’ve seen this movie before — literally.

Hollywood captured one version of this story in The Big Short. It wasn’t just a tale about housing; it was a parable about incentives and blindness. The banks packaged risk, sold it as safety, all while regulators applauded the “innovation.” And in the end, all the people most responsible for creating the instability were bailed out without any punishment.

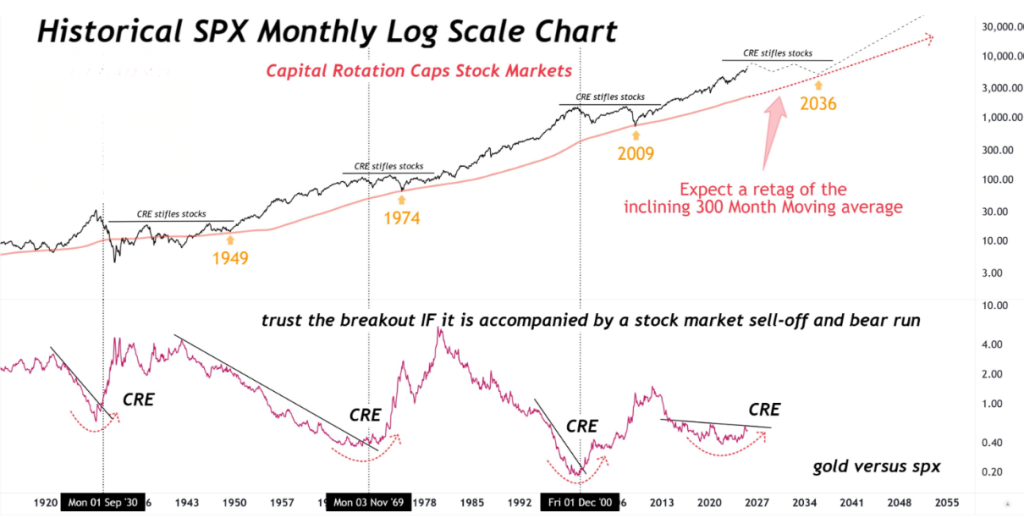

Over the last century, three major Capital Rotation Events (CREs) have followed the same script:

- 1929 — The Roaring Twenties ran on easy credit. When that credit collapsed, so did the illusion of endless prosperity. The Crash of 1929 wiped out fortunes, ushered in the Great Depression, and forced Roosevelt’s hand. By Executive Order 6102, citizens had to turn in their gold. He promptly raised the price from $20 to $35 an ounce, recapitalizing the government overnight.

- 1968 — Congress repealed the gold-backing requirement for Federal Reserve notes, breaking the final restraint on dollar creation. Gold demand surged, forcing the U.S. to raise its official price repeatedly as confidence in the dollar faltered. This resulted in Nixon’s ending of the gold standard in 1971.

- 2001 — The dot-com bubble burst, central banks slashed rates, and a new credit supercycle began. Real estate and derivatives replaced tech stocks as the speculative frontier. When that collapsed in 2008, gold led once again.

In the chart below, the golden dates listed on the top graph indicate the bottoms of the last three crashes. However, the dates discussed previously cover the causal factors that led to those Capital Rotation Events.

In the bottom graph, you can see the CREs more clearly, shown by the relationship between the price of gold and the S&P 500 (SPX). When the markets crash, it’s good to be in gold.

The Everything Bubble — The Correction has Already Begun

Every bubble begins with the same illusion: that more controls can replace consequence.

For the last fifteen years, that illusion has defined global markets and the financial system we live in:

- When the banks failed, they were bailed out.

- When debt grew unsustainable, we created more of it.

- When recession resurfaced, deficit spending disguised it.

Every major asset class now essentially runs on an assumption of increasingly unpayable debt. The banks don’t fear collapse because bailouts are normalized.

But credit is only as strong as belief, and that belief is starting to fracture.

The chart below shows the Buffett Indicator, which is the total U.S. market value divided by the GDP of America. The ratio range shown indicates the expected valuation; when the graph is below this range, the market is undervalued, and when it is above the range it is overvalued.

The last time the Buffett Indicator showed an overvalued market was at the dot-com-era peak. That ratio was just under 1.5, and we are now above 2. If the dot-com bubble created a crisis, then imagine the fallout from the Everything Bubble.

The institutions that engineered each bailout are now trapped by them. Raise rates, and they threaten the solvency of the governments and corporations that built empires on cheap debt. Cut rates, and inflation returns, eroding the currency they claim to defend.

That’s the trap of the Everything Bubble: the policy itself is the bubble. Each bailout demands a larger one to contain the side effects of the last. The cycle no longer produces growth; it produces dependency.

And still, the charts climb (at least on paper).

It’s easy to believe the line goes “up and to the right” when the ruler keeps stretching. As dollars multiply, every asset priced in dollars appears to rise, even if real value stagnates. Inflation doesn’t just lift prices, it falsifies progress.

If trillion-dollar bailouts can happen without riots in the streets, what’s the harm in the quieter transfer: siphoning wealth from savers through inflation? The public accepts it because it feels invisible. Purchasing power slips away in decimals, not decrees. The system survives, but only by consuming its own credibility.

That’s the correction already underway, not a sudden crash, but a gradual repricing of trust. The dollar, the debt, and the promises are all being marked down against the same benchmark it always has been: tangible value.

Gold doesn’t surge because of panic; it rises because everything else is being quietly devalued against it. It doesn’t default, dilute, or beg for bailout. It simply sits outside the system, waiting for the system to reset around it.

The reset has begun. Confidence will erode, capital will rotate, and what’s left at the bottom will look exactly like what J.P. Morgan described more than a century ago:

“Gold is money. Everything else is credit.”

The predictable market correction no one’s ready for isn’t just coming; it’s here.

We’re just measuring it in the wrong terms.

Measure the markets in Gold to get a reality check.